|

¡¡

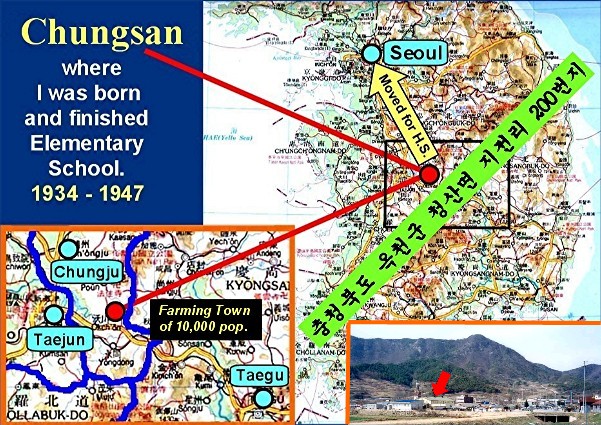

Chungsan

(Elementary School)

200

Jijonri, Chungsan-myun, Okchun-goon, Choongchung North Province. This is the

address where I was born and lived until I finished elementary school.

Chungsan was a relatively large farming town with about 20,000 population

when I lived there but I

was told there are only about 5,000 population now, as many people

moved to large cities. Chungsan is located at southern part of Choongchung

North Province at the middle point of Boeun and Yungdong. It is a part of

Okchun County but closer to Yungdong.

I

lived in Chungsan for 13 years until I finished Chungsan Elementary School.

However, I have no memory of my life before I entered the school and can

recall my life of 6 years only while I was attending the school. As soon as

I entered the school, there was the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor on 12/8

same year and the World War II had started. Therefore, most of my life at

the school in Chungsan until Korea was liberated when I was 5th. grade, was

wartime under Japanese occupation of Korea. During this time, it was really

a hard time for all Koreans with short supply of food and strict control of

Japan to win the war. Especially, at the end of the war, we were forced to

worship at Japanese shrine, delivery of rice and metals to Japanese

government, forced hard labors, draft to Japanese army, sexual salves for

Japanese army for girls, etc. etc.

My

family lived at Jijonree by the mountain, which was the central part of

Chungsan. My uncle (my father¡¯s elder brother) lived next door and both

our families were very rich and well recognized by everyone in the town. My

uncle passed the state exam as a scholar, but he didn¡¯t take a government

job. Instead, he spent time reading books at home and was well respected as

he was the eldest among the nobles in the town. Other people knew us as the

most civilized family because my father, very unusually at the time, went to

U. S. A.

and studied in the college there. We were the only one who had radio and a

record player in whole town. With this academic background, my father and

uncle did not take any job and they didn¡¯t obey the Japanese order to

change the family name to a Japanese name. However, the Japanese law

enforcement couldn¡¯t do anything about it since they were a family of

dignity. (So my name was still Cho To-Rin - Japanese pronunciation of Cho

Dong-In, during the Japanese occupation.) One day, at school, the teacher

questioned me about this saying ¡°Are you a Japanese or American?¡± (I

guess the teacher asked this question because we did not change family name

and my father looked like a pro-American with his academic background in U

.S. A..)

On

that day of Chungsan, during my elementary school years, what I remember

most vividly was the Jesa (a religious service to the ancestor). I was

trying to stay up until the Jesa finished, which was held right after

midnight. I wanted to stay up for the food, but my boyish activities from

earlier in the day drove me to sleep almost every time. I remember it was

less than 5 times I could stay up to have nice food even though there had

been Jesa once a month in average, since we were worshipping back to the 5

generations (twice for each generation for grandfather and grandmother). I

asked my mother to wake me up, if I fell in sleep, but she did not as she

could not wake such a small boy up so tired and sleeping deeply and I

usually whined the next morning. Especially, at the end of the Japanese

occupation, food was scarce. Even people as rich as our family lived on rice

in water with shrimp sauce only and it was very rare to have some meat. So

the food from Jesa was a good chance to have a tasty meal. (I bet the

generation of today would never understand what it means to be looking

forward to Jesa for the food.)

In

the agricultural society, the income is limited by the the size of a farm,

even during a year of abundance. Therefore, the only way for the landlord to

acquire wealth was to save money. While spending is a virtue in

industrialized society of today, to thrift was desperately required on that

day, even for a rich family. One of my cousins (I forgot his name) asked his

father for a new pencil. He was scolded by his father who said ¡°My pencil

lasted for three years and you are asking for a new one in a few months.¡±

But I know my uncle usually has used a brush instead of a pencil and that is

why he can use a pencil for more than 3 years, or even more than 5 years. I

stress how the rich people in the old days were so thrifty.

Usually,

at my uncle¡¯s house, I played with my cousin, Dong-Bun as we are the same

age. But I also spent a lot of my time with Hun-Koo and Kyung-Koo¡¯s

mother, the wife of the 2nd son of my uncle. She was always kind

to me and told me so many fun stories in her room of my uncle¡¯s house. She

even taught me how to knit a sock with a bulb in it. Several decades later,

during the Cross

U.

S. A. Trip in 1975 in

U. S. A.

, I visited her house in

South Bend

, Chicago. We were so happy to see each other again. Now, since she has passed away,

I¡¯ve missed her very much.

Regarding

my uncle, since he was so old and always stayed in his room separated from

inner part of the house, I don¡¯t remember him talking to his family very

often. I do remember him folding his hands behind his back, walking back and

forth in his room and saying, ¡°Damn it! Damn it!¡± I had no idea whom he

was talking about. I guess he may be blaming at pro-Japanese Korean or some

bad guy in the town. My aunt always looked sad most of times though I

didn¡¯t know why. She was always so kind. Perhaps, she looked so sad

because my cousin, Dong-Bun was deaf-mute. Anyway, she looked sad most of

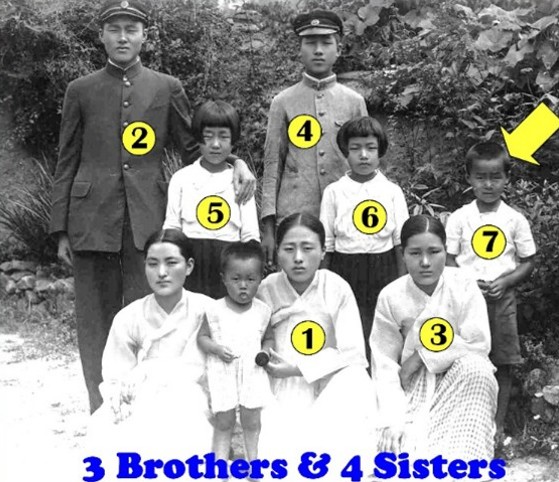

times. My cousins Dong-Woon, Dong-Bun, and nephew Hun-Koo, Kyung-Koo all

lived in my uncle¡¯s house and my elder sisters Dong-Sun and Dong-Hyun were

living with me. The older children were studying in

Seoul

. In the year

Korea

was liberated, my eldest brother was released from Seodaemoon Jail and

recuperated at home. Sung-Koo, his son, came to my house at the same time so

it would be 2 years for him to stay at Chungsan.

One

more thing I can remember is the rice chest in the middle of the front yard

of my uncle¡¯s house. It was about 7¡¯ x7¡¯ in widths and about 15¡¯

high. Every fall, the rice was poured into the top and the family took rice

from the bottom. Because the chest was so big, they couldn¡¯t have fresh

rice from the current harvest and my uncle¡¯s family came to my house from

time to time to taste fresh rice. We also had a big rice chest in our back

yard but it was much smaller than the uncle¡¯s and we had many more chances

to eat fresh rice, because my mother cooked fresh rice too in fall often.

I

think I resemble my father in many ways. The One is I am very talkative as

my father. My brothers and sisters are also very talkative. When my elder

brother Dong-Han brought his friend home and introduced him to my father, my

father talked them so long that their knees hurt. At the whole town of

Chungsan

, only my family had a radio. After dinner, all the elders of the town

gathered at my house to listen to the radio very often. It looked like a

town conference every evening. I know My father was an officer of the

Chungsan Consumers'

Credit Union for a while but I don¡¯t remember this very well as it was

when I was too small to remember. He also took charge in Keibodan, an agent

of Japanese government, which combined fire fighting services with the civil

defense corps. I guess he took that position to avoid the blame of not

changing our family name to Japanese name.

I

still don¡¯t understand why my father choose to study the difficult and

unpopular subject of Geology in

America

which I never got a chance to ask him. He never thought of being employed.

He was very interested in farm business and managed a Gyejang (a chicken

farm) where he kept more than ten pigs and thousands of chickens. With a

hatching machine, he used to hatch up to 2000 chicks at a time. His goal was

to win the 1st prize at the

Okcheon

County

Fair and Choongchung

North

Province

Fair. I believe we have had hundreds of eggs every day but I don¡¯t think

we have ate a lot of them, because they have been all packed in apple boxes

and sent to Seoul where my eldest brother, Dong-Joon has had to pick them up

at Seoul railroad station every morning to deliver them to the wholesaler.

Since my father used chicken food of the highest quality, my mother said it

has never been profitable. He was just satisfied with the result of raising

good chickens that lay more than 365 eggs a year.

Other

than livestock, we owned two areas of pear orchards, two apple orchards and

two peach orchards. Also, we planted watermelon, melon, strawberry, grape

and all kinds of fruits at the corner of the chicken farm. I was skilled at

picking out good fruits. The crows were also very smart choosing good pears

and apples. I figured out that the rotten pear and apple somehow tastes

better.

I

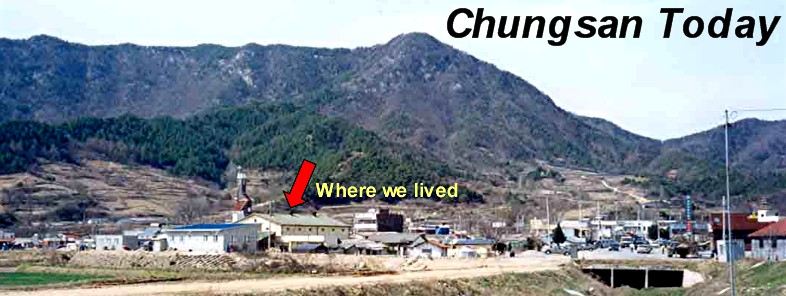

did not realize that the Chungsan was such a beautiful and peaceful place,

when I was living there, just like a fish does not appreciate the water it

lives in. Our village was surrounded by mountains with full of pine trees

and the center of the village was Chungsan stream, which was the source of

the Gumkang

River. Some areas were about 30 feet deep and other areas were shallow enough for

kids to play in. The water was so clean that you could see the sand 20 feet

below through the water. Clean and white sand ran along the stream with big

and small rocks scattered here and there. My friends and I swam, fished,

cooked, and ate at the stream. Some kids who swam well tried cannon balls

from the cliff. What a lovely place¢®¦. However, when I visited

Chungsan again not long ago, I was very disappointed to see this beautiful

stream water turned into a small filthy brook because of so-called

civilization.

I

also remember that there was a big rock (20¡¯x 20¡¯ widths and 30¡¯

height) at the hill behind my house. I used to climb up that rock and

enjoyed the view of Chungsan village. During the summer, when it was too hot

day, I went up there with my sister to cool down. On the night of full moon

in January, we put some small dry woods in a can with many small holes,

burnt it, and swung it round and round. But it was a dry winter season and

we were scolded by adults, because it was dangerous to cause fire, as the

livestock¡¯s pens and pine tree woods were very close to the rock.

Mostly

we played at the top of this rock. However, if you keep going up around 100

yards, you can find a 200 square feet open space lawn, where you can have

better view of Chungsan village. On summer evenings, after dinner, this was

the best place for taking a walk.

I

am not sure what the distance is between Chungsan and Okcheon (Chungsan is a

part of Okcheon County.), but I know it is longer than the distance between

Chungsan and Youngdong (Youngdong County

) though. Therefore, Youngdong was the gate to Chungsan and the Chungsan

folks rode a train to

Seoul

at Youngdong train station rather than Okcheon. The bus to Youngdong came

once a day but, when I was about to finish elementary school, it came twice

a day. The distance between Youngdong and Chungsan was about 15 miles and

the other way north, the distance between Chungsan and Boeun was 15 miles

too. At about middle point between Youngdong and Chungsan, there is Yongsan

where our family cemetery is, to where we usually walked to visit family

cemetery once a year on the day of Choosuk rather than to wait for bus. I

believe it was 1946 Choosuk, when small Sung-Koo at the 1st.

grade of elementary school and I at 6th. grade walked together to

Yongsan to visit his father¡¯s grave and talked a lot of things on the way

and back.

If

you go about 3 miles toward Boeun, you will get to Chongsung. My school once

took a field trip there where we found a small opening in the wall that led

to a spacious cave. It probably looked a lot bigger than actual to me

because I was so small.

Like

everybody has a nostalgia of his home, I miss Chungsan as the most peaceful

place in the world, where no one would hesitate to sing postural songs.

However, ten years ago when I visited there, I was so sad to see a lot of

these beautiful and peaceful Chungsan was destroyed by modern civilization.

I

know it would not make any sense to compare the time of my elementary years

with current elementary school kids with so many toys to play. What we

played with were: cardboard papers size of 1.5"

x 2.5"

printed with various pictures (We bought them some but they were too

expensive for us to buy so we made them out of newspapers later), two twigs,

China

marbles (we needed to buy them), and top spins. Girls made pockets with a

piece of cloth, put some grain in it, sewed it up, and tossed it around. You

could be popular if you had a hoop (metal bicycle wheel) to drive. We went

sledding on the ice in the winter and swam in the stream during the summer.

And, those were all we could play with. Since Chungsan was such a small

village, there weren¡¯t any book store nor toy store. The only books we

could read were school text books and my brothers studying in Seoul

never brought me any present when they come home during summer and winter

vacations. (Probably, they didn¡¯t have any extra money to buy toys for

younger brother or the gift itself was not as popular as today.)

Because

I was suffering with skin disease, every summer vacation I visited my eldest

sister¡¯s house in Daejon and tried a hot spring cure at Yoosung. I recall,

when it was time to come home, my sister usually bought me lots of comic

books and my friends were so jealous of me.

At

school, they held an athletic meeting and a class day every year. I hated

the athletic meeting but the class day was my favorite. Since I didn¡¯t

have good coordination, I was always last place in athletic sports. But, I

performed remarkably on class day in drama and oratorical contests and I

believe I have represented my class for the oratorical contest every year.

I

had a very interesting experience at elementary school. I won 1st

place at the school oratorical contest and they let me participate in the

county contest. I practiced so hard that my voice became hoarse. As it got

closer to the contest day, my voice still didn¡¯t come back. My mom treated

me with raw eggs to heal my hoarseness. On the contest, my voice was OK for

the first 2-3 minutes, but then it got hoarse again. But, I completed my

speech without a voice all the way any way. I couldn¡¯t believe myself I

had the nerve to continue to finish. When the contest was over, they

announced me as 3rd place. I was told the judges counted my

confidence to continue without a voice. I am still very proud of this

prize.

My

best friend at elementary school was Sun-Young Kim who was the 3rd

son of Mr. Kim¡¯s family. Mr. Kim had passed the national exam for a

government officer but did not take job either as my uncle. He was also a

good friend of my father¡¯s and his family and mine were acquainted very

well. Sun-Young and I were rivals in the class for 1st place as

well as bosom friends. I am so sorry because my buddy Sun-Young followed his

brother Sun-Joon, who was communist and sick, to north Korea to treat him

when the north Korean army retreated in September 1950. Since that time on,

I never saw him again. (At that time, anyone who followed the north Korean

army thought they would be able to come back when the north Korean Army won

the War.) Earlier, his eldest brother Sun-Ho who was also a good friend of

my elder brother Dong-Han, was recruited as a student soldier by Japanese

army and was killed on the South East war front. Needless to say, his

parents were heart broken with the loss of all their sons more than I still

miss my best friend Sun-Young, as if I have lost my real brother.

Since

it was close to the end of the Japanese empire, the situation was turbulent

for Korean people. Even young elementary school boys like me were not an

exception. My school was the only school in Chungsan, so the Japanese

government imposed forced labor on boys and girls in the school. Under the

name of Labor Service, every student over 2nd grade had to weed,

plant, and harvest at farming fields of the village. They had to step on the

barley field so that it wouldn¡¯t freeze in winter, collect weeds for

fertilizer and dig out dead pine tree roots for fuel.

The

latter job was too hard for me to do, so my father¡¯s farm servants used to

help me. Since most young men in a rural community like Chungsan were

recruited as laborers in factories or mines or soldiers of the Japanese

Empire, it was very short handed. All chores like these were imposed on

10-year-old children like us. I was not very good at using sickles and I got

cuts on my fingers. I still have a scar on my finger. They also made us

collect and submit lice or rat¡¯s tail. They forced us to deliver all kinds

of metal such as ornamental hairpins, brass spoons and silver wares to

produce weapons. So we got used to using wooden spoons and chopsticks.

Moreover,

once in a week (or a month?), no matter how the weather was, we would walk

half a mile from school to the Japanese shrine to worship. If it was a very

cold day, we had a very hard time. Every morning at school, we would shove

all chairs and desks off to the back, kneel on the floor and recite the two

Jokugo (The Japanese Emperor¡¯s manifesto to the Japanese citizen and a

lecture regarding the education), then we could start class. Since these

Jokugos were prepared by most famous Japanese scholars, it was too hard for

us to understand them even though I could recite them thoroughly.

Japan

by all means tried to brainwash Korean people so that we could forget our

original nationality.

As

it got closer to the end of World War II, most of the principals at school

were Japanese, but ours was Korean. To hold his position, he was ready to do

anything when duty called. I remember he tried to outperform all the other

principals. There are three ways of greeting in Japanese such as

¡°Ohayogozaimasu¡± for morning, ¡°Konnichiwa¡± for day time, and

¡°Konbanwa¡± for evening. Also, they say ¡°Sayonara¡± which means

¡°Good Bye.¡± But in my school, the greeting for every situation was

¡°Kachimatsu¡± which meant ¡°We will win the War.¡±

He

proactively encouraged, persuaded and even threatened people to volunteer as

a student soldier for man and soldier¡¯s sexual entertainer for a girl. In

a morning session, he even made announcement to present his head, if Japan

lost the War. When Japan

actually lost the War, the village people came to his house, blamed him for

their son¡¯s and daughter¡¯s life and asked his head. He had to run away

and hide out for several years. (I heard several years later, when

Korea

formed a new government, a rumor that he was hired as a Choongchung

North

Province

school commissioner.)

When

the Japanese government retreated from Korea, my elder brother Dong-Han, who was forced to serve as a Japanese soldier,

came back. I saw him destroying all the Japanese record disks patriotic to

Japan

and of military marches at the school playground. He also chopped all the

cherry trees with friends that were planted along the road to the

Chungsan

Elementary School

as the cherry flower is a national flower of Japan

.

My

elder brother, Dong-Han was drafted as a student soldier when he was a

student of

Bosung

College

which is a Korea

University

now. He served as a Soviet-Manchuria border guard and returned home when Japan

was defeated. It took him three months to walk back to Seoul. Even though it was bitterly cold in Manchuria, he was very lucky to serve

on the border, otherwise he probably would have been killed at the

South East Asia

War front. Most of those who served there got killed. After the return to

Chungsan, he served as a

Chungsan

Elementary School

teacher for a while and moved to

Seoul

as the whole family moved to Seoul.

My

eldest brother was a student of

Kyungsung

Technical

High School

which is now the

Engineering

College, Seoul

National

University, where I have graduated. His major was textile engineering. He was

consigned to prison since he was involved in the ¡°Hun-Young

Park¡± incident, which was an anti-Japanese movement. After the liberation from

Japan, he was released from jail but contracted tuberculosis in jail. At that

time, there was no cure for the tuberculosis and came home with family, wife

and Sung-Koo. Since there was no textbook available written in Korean yet,

only the teacher had one. My eldest brother let me borrow the textbook from

teacher and copied it into a note book overnight. So I was the only student

who had a textbook. I still remember such a perfectly copied textbook with

beautiful handwriting just as printed. My mother was so desperate to cure

him that she called a female shaman for help. A female shaman entered my

brother¡¯s room and performed an exorcism, shaking a twig over my brother

who was laying down on the floor. But as soon as my brother saw her, he

jumped up from the bed and slapped her on the cheek. The female shaman ran

away, scared out of her wits. Since my brother was an engineer, it was

absolutely out of the question for him to rely on shamanism, just as I

don¡¯t. Less than half a year later, my brother passed away and his son,

Sung-Koo, and I used to perform Sangshik (offering of meals to a departed

soul) twice a day.

Epilog:

Just after the liberation, too few people could command in English. Since my

father spoke English well by his American education, he was hired as a

counsel for the

Choonchung

North

Province

office of U.S.

military government though his major task was interpretation. While he was

at this job, he founded

Chungsan

Public

Middle School

persuading the U.S.

military government.

¡¡

|